Message Reliability and Waku API

An introduction to message reliability and the role of Waku protocols in ensuring it.

Waku provides a suite of protocols to enable Denial-of-Service (DoS) protected, peer-to-peer message routing and access to said peer-to-peer network for resource-restricted devices.

Those protocols have been designed to solve message routing, focusing on privacy and censorship resistance, hence implementing a peer-to-peer decentralised topology.

While libp2p gossipsub and Waku relay are reliable in a well-connected environment, those protocols remain only as reliable as their underlying transport (TCP, WebSocket).

Building working applications over Waku is possible, but end-to-end reliability is up to the application developer. Those strategies can be heavy on resource consumption. Moreover, the redundancy, dynamic mesh of peers, and gossiping that provide Waku Relay with its reliability are not present out of the box for light client protocols.

These are overheads for application developers who would rather focus on application logic than connection management for Waku.

Definition

We define reliability as:

- There is a high likelihood of messages being sent and received by a node in a timely fashion

- Awareness of liveness state:

- Was a message sent or not sent, or do we not know (yet)?

- Can I receive messages at the moment?

In the context of Waku, there are three layers to reliability, from lowest to highest in the stack:

- Transport: Reliability within the libp2p layer, constituent transports, and protocol stack, including peer discovery.

- Peer-to-peer: Reliability within the Waku message routing and discovery layers between a local node and its direct connections to remote peers; said peers may have no functional relevance to the application.

- End-to-end: Reliability within the application layer, on top of the Waku message routing and discovery layer. This layer is used primarily for the application to know whether the intended recipients received messages or whether incoming messages are missed, regardless of the number of hops away.

Transport-level reliability

Apart from setting the correct parameters for TCP usage, we can do little to improve its reliability beyond what can be done in the underlying libp2p library. However, new transports, such as QUIC and WebTransport, can be introduced to improve on TCP/WebSocket.

Libp2p-gossipsub usage is a similar case. We can tune some parameters at Waku level. We are also reviewing go-libp2p-gossipsub and nim-libp2p-gossipsub behaviour in desktop and mobile environments to answer questions such as: can disconnection detection in gossipsub be improved?

No major changes are expected at this layer, but understanding the inner workings will enable a more efficient strategy at the next layer.

Peer-to-peer reliability

By peer-to-peer reliability, we mean message reliability between reachable nodes in the network. At this level, we can better understand the connectivity state, whether outgoing messages are propagated across part of the network, and whether we are receiving messages from the network. With every peer implementing peer-to-peer reliability strategies, heuristics of end-to-end reliability will increase but cannot be guaranteed.

Filter and light push protocols already have baked-in reliability mechanisms such as filter ping and light push ack messages. However, this is not sufficient. Relay redundancy must be replicated in light client protocols, especially in a decentralised topology.

Moreover, while gossipsub is very reliable on a stable connection, its mechanism to detect disconnection has practical limitations.

Strategies to increase peer-to-peer reliability heavily depend on the new store v3 protocol. This protocol enables store responses to only contain message IDs and is more cost-savvy than store v2, which replies with the full message payload. A mix of regular store queries, libp2p ping, filter ping, and enhanced peer management will increase p2p reliability. Our RFCs will also define this. However, these strategies are likely to be at the cost of increased bandwidth usage and high connections requirements.

End-to-end reliability

In the user's eyes, meaningful reliability means ascertaining whether the intended recipient of their messages has received them and ensuring that, as a recipient, they do not miss messages.

End-to-end reliability is the way that specific users can communicate reliably across the network, in contrast with peer-to-peer reliability, which is focused on reliability between somewhat random reachable nodes in the network. It also ensures that nodes that are multiple hops away from each other are able to exchange messages reliably.

MVDS is an end-to-end reliability protocol. It is used in the Status application. The main caveat is that it only handles communication between two people and cannot be scaled without drastically increasing bandwidth usage.

With Status Communities, we want to enable thousands of users in a given community, so a new protocol is needed to enable end-to-end reliability among community participants.

Encryption

A protocol that enables users to know what message they missed or need to resend is likely to leak information about their social graph, even if the message content is encrypted. This is why it is essential for the metadata generated by an e2e reliability protocol to be encrypted and only accessible to the intended participants.

For 1:1 chats, Status' encryption provides confidentiality, integrity, authenticity, and forward secrecy. It adapts Signal's double ratchet algorithm to a decentralised topology. Unfortunately, this scheme does not scale to large groups as it only enables 1:1 scenarios. It can be used in small groups by setting up encrypted channels for each participant, but this strategy creates overhead that becomes impractical for larger groups.

Large groups (communities) currently use symmetric encryption. While it includes end-to-end encryption of data and metadata, it does not provide forward secrecy. An encryption scheme such as MLS should be used to set up a secure channel between hundreds or thousands of participants. MLS provides native group encryption that can be scaled to approximately 50,000 clients.

Unfortunately, MLS does assume the use of some central services, so further research is needed to design a secure group encryption algorithm that works in a decentralised topology.

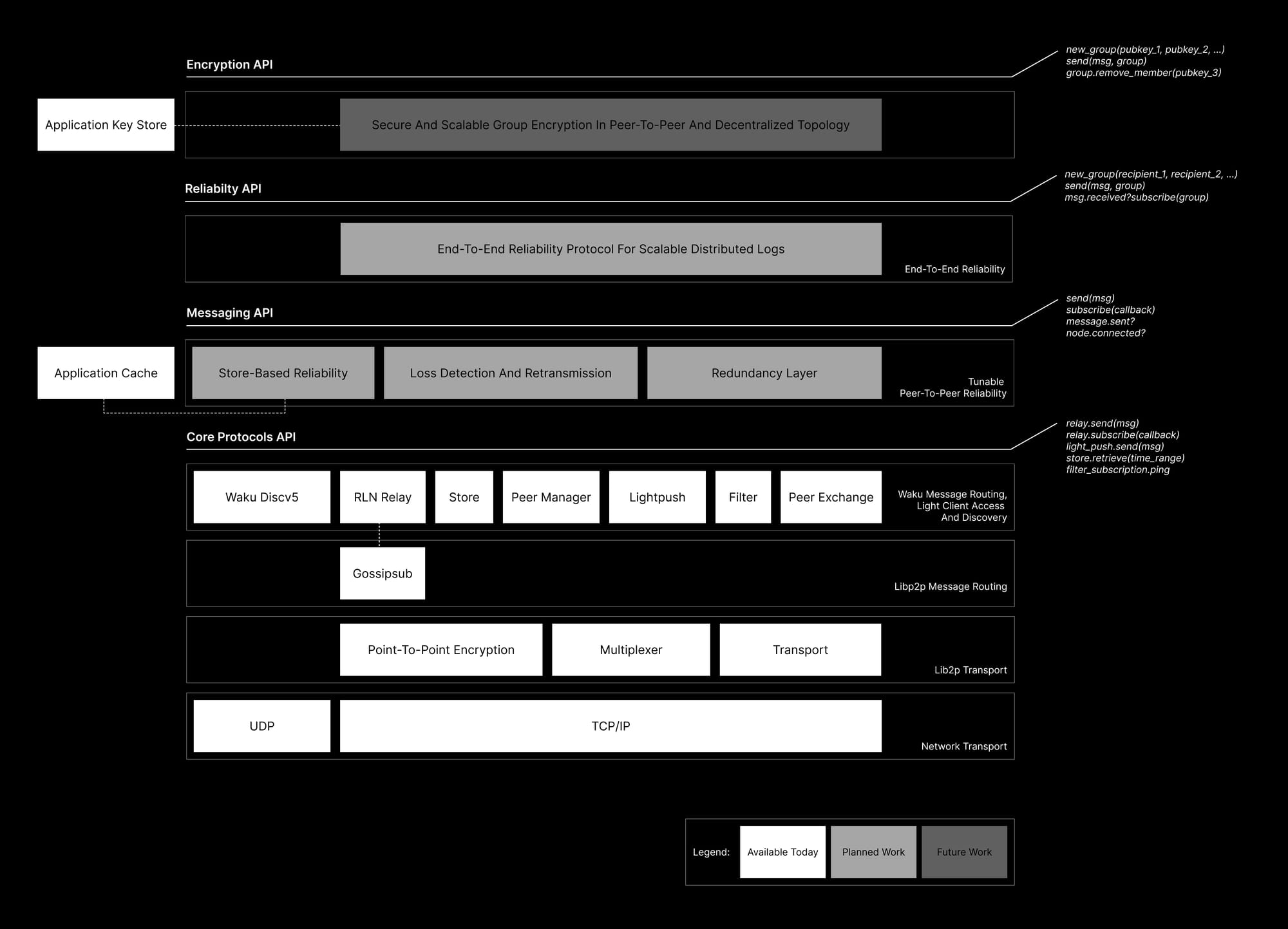

APIs and Timeline

The Waku team is currently focusing on providing the reliability layers outlined above. We will deliver this work through new APIs for application developers that abstract complexity and use the existing Waku protocols with new reliability guarantees and heuristics.

Core protocols API

The API currently available to developers provides direct access to the Waku core protocols. While it is functioning, it has several caveats:

- Reliability: As discussed, these protocols are as reliable as their underlying transport.

- Protocol knowledge: Developers need to understand each protocol API and its behaviour.

- Encryption: Encryption is provided in the library, but its application is left to the developer.

As part of the work outlined below, the core protocols API will be improved to ensure that reliability concerns are isolated in a different layer (separation of concerns principle). The first iterations of Waku Store improvements (v3) have recently been delivered, and further work on the peer manager is expected to enable peer-to-peer reliability.

Messaging API

We are currently working across Waku implementations to abstract peer-to-peer reliability strategies to provide them in a new, simpler API. Ideally, an app developer wants to send, receive and _retrieve _messages with fair reliability. They should not be concerned by the underlying protocols and how Waku handles this.

This is the most basic API. It should improve the_ status quo _and be used by developers when higher APIs do not fit the purpose (e.g., broadcast messages, ephemeral messages).

Developers can use this API without any application context, and it enables them to solve some of the previously stated caveats:

- Reliability: Improved disconnection identification and handling, using store queries to check for sent and missed messages, using multiple connections for resource-restricted protocols (light push, filter).

- Protocol knowledge: Core protocols are abstracted to provide simple verbs such as relay versus light client mode, send message, receive messages, and retrieve past messages.

- Encryption: same as core protocols API.

We aim to deliver this API and integrate it in Status applications by the end of Q3 2024, with earlier commitments on specific deliverables.

Reliable Communication API

With this API, the user gains more certainty on message delivery. However, it does imply several assumptions, such as knowing the number of recipients and their identifiers.

Such API would resolve most, but not all, caveats:

- Reliability: Waku uses a new end-to-end reliability protocol to provide better feedback about the status of a given sent message or messages for which the user is the intended recipient. While transient unknown states may still occur, Waku software will clarify whether the application or user should retry.

- Protocol knowledge: The set of _verbs _from the messaging API still applies. However, the API will need more application context to be passed (e.g., some identifier for the message recipients) to enable the developer and user to be more certain about the message status.

- Encryption: same as core protocols API.

Research on this has started. While we expect delivery to be iterative through Proof of Concepts, we committed to delivering a working protocol and integrating it into the Status application by the end of 2024.

Encryption API

With the reliability API, developers still need to reason about encryption. Waku should provide a scheme that enables encryption with forward secrecy, plausible deniability, and scalability for large groups in a decentralised topology out of the box.

Developers should then only need to pass the public keys (or other cryptographic artefacts) of group members for Waku to negotiate a secure channel and provide end-to-end encryption. This would allow the end-to-end reliability protocol to operate without leaking metadata.

In this context, content topics are also likely to be handled by Waku software to ensure developers do not inadvertently leak metadata.

The Vac cryptography team is already conducting research on this topic. The timeline for integrating the result in Waku currently needs to be defined.

Conclusion

Users and developers expect high reliability from the communication systems they use. When operating in a peer-to-peer domain, developers cannot always apply the traditional strategies used in centralised architecture.

While the margin to make the existing Waku protocols more reliable is thin, it is possible to build new layers on top of them to achieve higher reliability. For the next six months, the Waku team will focus on designing the said layers, which will then be integrated into the Status applications and included by default in the Waku SDKs.